WHEN LAGO WAS LUCKEY

By: Ray Burson

THE FIRST TWO PAGES OF THE ACTUAL DOCUMENT ARE SCANS, THE TEXT IS NEXT, THIS IS NOT SCANNED AND LINKS ARE PROVIDED TO FOOTNOTES AND IN THE FOOTNOTES LINKS ARE PROVIDED TO WEBSITES THAT ARE REFERENCED. CLICK ON THE FOOTNOTE NUMBER TO GO TO THAT FOOTNOTE, WHEN IN THE FOOTNOTES CLICK ON THE NUMBER TO RETURN TO THE SAME POINT IN THE TEXT. THE PHOTOS THAT FOLLOW THE TEXT ARE ALL SCANNED FROM THE DOCUMENT.

To see a oral history of Ray Burson go to

the

Rutgers

Oral History Archives

New Brunswick History Department

http://oralhistory.rutgers.edu/Interviews/burson_ray.html

The February 16, 1942 attack by German U-boat 156 on the Lago Oil & Transport Company’s refinery on Aruba, Netherlands Antilles has been well documented. Lago’s bi-weekly publication, The Aruba Esso News, carried a series of articles titled “The War Years at Lago” in 1946 and in 1962 then editor William Hochstuhl wrote a 20th anniversary article, “German U-boat 156 Brought War to Aruba February 16, 1942.” This in-depth report was republished by Clyde Harms, along with eyewitness accounts and the English translation of a portion of the submarine’s log book, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the attack in 2002.

One can get additional information from the histories of the various military units that served in Aruba, from books, and from numerous magazine and newspaper accounts. In his book Aruba Past and Present (1961), Dutch historian Johan Hartog devotes ample space to Aruba during the war years. U-boat war diaries (KTBs) are available from the National Archives; War Operations Reports (BdUs) can be found on the Internet. For several years a U-boat roundtable has been meeting periodically to discuss the details of the attack itself, especially those first shells fired at a land target in the Americas in World War II.

A review of this recorded history might lead one to the conclusion that there is nothing more to be said on the topic. Nevertheless, many details about those early war years in Aruba have been scattered, misstated, distorted or as yet unreported by researchers in regard to the ships, planes and people involved and decisions made.

This paper will attempt to bring together the disparate strands of a larger story including information from previously classified telegrams from the U.S. Consulates in Curacao and Aruba to the Department of State in Washington. The result, it is hoped, will be a comprehensive portrait of the perils of that chaotic time and how events transpired to make February 1942 a lucky month indeed for Lago and Aruba.

One can mark Aruba’s direct involvement in World War II from May 10, 1940, when Germany invaded Belgium and the Netherlands. That same day the German freighter Antilla was scuttled at Malmok and its crew sent to internment camp on Bonaire along with crews from seven other German ships captured in Curacao by boarding parties from the Dutch light cruiser Van Kinsbergen. Other German nationals and Dutch quislings residing in the Netherlands West Indies were also rounded up. That too was the day when the French auxiliary cruiser Primauguet arrived in Oranjestad harbor from Martinique and disembarked 180 French marines to support the small Dutch garrison.[1]

Lago, however, dates its participation in WWII from September 3, 1939 when the refinery started furnishing petroleum products for the Allies. That year Lago produced 227,600 barrels per day, which was 27% of Standard Oil’s world-wide output. The main product was 100-octane aviation gasoline and the primary recipient was Great Britain. Having the superior fuel was considered the critical edge that gave the RAF victory in the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940.[2]

Thus it was in the summer of 1940 that Britain moved to protect Lago. The Netherlands had surrendered to Germany on May 14 and France had given up on June 22. When the French marines left for Martinique aboard the Estrel on July 6 they were immediately replaced by 120 British troops sent from Jamaica. The Van Kinsbergen was called in to observe the departure because the Aruban authorities feared the now Vichy French might try to set the fuel depots on fire before leaving. On September 3rd the British unit was succeeded by 520 Scottish soldiers of the 4th Battalion of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, many of them veterans of Dunkirk and Flanders.

Their commander was Major Colin “Tiny” Muir Barber (1897-1964) who, at 6 foot 6 inches, was the tallest officer in the British Army. He would be promoted to Lt. Colonel on Nov. 4, 1940 while in Aruba, later lead the 15th Scottish Division in France in 1944 and eventually attain the rank of Lieutenant General.[3]

One might conclude from the events of the time that the French and British forces were sent primarily to protect the island from attack by Nazi Germany. That was not the case according to U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull in a meeting in his office with Japanese Ambassador Horinouchi on May 16, 1940.

Hull later wrote, “The Ambassador then proceeded at great length to question and cross examine me about the Netherlands West Indies, comprising Curacao and Aruba. I said that… As soon as this Government learned of the fact that British and French vessels patrolling the waters near Curacao and Aruba were offering potential aid to the Netherlands Government in preventing possible sabotage and possible armed expeditions from the mainland intended to seize the governments on one or both of these possessions,… this Government proceeded to assemble the facts as expeditiously as possible… I further stated that it was my understanding that the British and French patrols were in no sense interfering with the Netherlands governments on these two islands, but were recognizing the authority of these governments during the brief, temporary time deemed necessary to aid in safeguarding against the dangers already mentioned…”[4]

(Author’s note: The Japanese had their eyes on the Netherlands East Indies and were most interested in the ability of Dutch colonial forces to offer resistance to an invasion. In June 1929 Venezuelan insurgents led by Rafael Simon Urbina made an unsuccessful surprise attack on Curacao. The U.S. was opposed to the occupation of any Western Hemisphere territory by the armed forces of other belligerent powers.)

The next 18 months was a relatively calm time in Aruba. A coastal battery was constructed at Juana Morto and test fired its guns on May 17, 1940. An artillery battery of the Dutch colonial army arrived from Curacao in December 1940, anti-aircraft guns were placed in Lago refinery and blackouts were practiced at Lago and Eagle refineries.[5] By mid-1941 Aruba had a total of 889 troops, including 612 Cameron Highlanders according to a July 11 memorandum from U.S. Army Brigadier General Sherman Miles (G-2) to the Army Assistant Chief of Staff.

In a post-war article, the Lago refinery biweekly publication Aruba Esso News gave this opinion of the British troops quartered in Sabaneta: “Veterans of Dunkirk, they came virtually without equipment of war, and were generally thought to be here recovering from their Dunkirk experience. Their kilts, parades and bagpipe band were a never failing show to take the residents’ minds off their war worries.”[6]

Looking back from a vantage point of over sixty years, one sees a Caribbean complacent on the eve of war. (Perhaps it was because of the protection offered by the Third Neutrality Act of 1937, and the October 1939 Declaration of Panama which established a safety zone around the Americas.) Although prevention of sabotage was one reason given for having the Scottish soldiers on Aruba, there does not seem to have been any great concern about the wide influence of Nazi Germany in Latin America. The first Nazi party in Latin America was established in Paraguay in 1931. The German air force had advisors in Bolivia during the Chaco War with Paraguay in the 1930s, they established the forerunner of Avianca airlines in Colombia and the first airplane to be seen in Aruba was the German seaplane “Idoor” which landed in Oranjestad Harbor on July 4, 1925.[7] They had well-developed intelligence networks in Mexico, Chile and Argentina. Spain’s fascist, pro-Nazi government had strong ties to its former colonial empire and Spanish tankers plied the Caribbean under the cloak of neutrality, providing the Third Reich with maritime intelligence reports. (The Franco government also had a history of supplying German U-boats.[8])

When France fell, pro-Nazi Vichy France came into being and had naval forces under Governor Admiral Robert in Martinique and Guadeloupe and controlled French Guiana. As soon as the U.S. entered the war, Army Air Force planes began flying daily patrols out of Puerto Rico “to prevent the French warships anchored in Fort-de-France harbor on Martinique from sailing to join the German navy.”[9]

The U.S. War Department noted that Aruba and Curacao had certain strategic aspects in addition to refineries. Willemstad, for example, was an important bunkering station for commercial shipping companies operating routes between Europe and the Panama Canal. The Department’s War Plans Division drew up Rainbow 5, a comprehensive action plan to implement if the United States entered the war. One of the action items was that U.S. ground forces would relieve British troops on both islands. Before this could be done, however, acquiescence of the Netherlands Government in London would have to be secured by the British Government.[10]

ARUBA’S WAR BEGINS

At Lago there was still a feeling of calm even after the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. While the U.S. entry into the war increased the possibility of action, the general opinion was still “it can’t happen here.”[11]

In Washington the main threat to the Caribbean region seemed to come from Japan. There were reports that two hostile aircraft carriers had been sighted off the west coast of Mexico and the Panama Canal could be a target. On December 12, Secretary of War Henry Stimson discovered there was no unity of command in Panama. It took a week to decide that the Navy should be in charge. Meanwhile, the commander in Panama, Army Air Force Lieutenant General Frank Andrews, urged that his ground and air forces be reinforced. That was given priority and by the end of December the forces under his command had risen to 39,000 men. Thus the first major deployment of forces to the area was based on the possibility of a carrier raid from the Pacific.[12]

Support for Aruba and Curacao seemed to be in slow motion in December and January. At the Arcadia Conference in Washington between Churchill and Roosevelt, the parties concluded on January 13th that, “the relief of Aruba and Curacao, subject to Dutch concurrence is to be completed before the end of January.”[13]

Fortunately for Lago, the military planners were ahead of the diplomatic negotiators. Two artillery detachments were activated on December 23 at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. Force 1280 was scheduled for Aruba and Force 1291 was to go to Curacao.

Military historian William C. Gaines would later write, “In late December 1941, Batteries A and F, 252nd Coast Artillery, along with 2 officers and 35 men from Battery G, the regiment’s searchlight battery, were alerted for overseas duty. By January 1942, the detachment had departed for Camp Shelby. There they were attached to Force 1280 and Force 1291 and prepared for deployment to the Netherlands West Indies.

“In addition to Battery A, 252nd C.A., the Aruba Force… consisted of Force HQ and Service Company; Company C, 166th Infantry; the machine gun platoon of Company D, 166th Infantry; and part of the 213th C.A. (AA), consisting of the maintenance section of HQ Battery, 2nd Bn., a platoon of searchlights from Battery A and Battery G with 37mm automatic weapons. The force’s total strength was almost 40 officers and over 800 enlisted men. The Curacao Force was substantially larger (and)… totaled 66 officers and over 1,400 enlisted personnel.”[14]

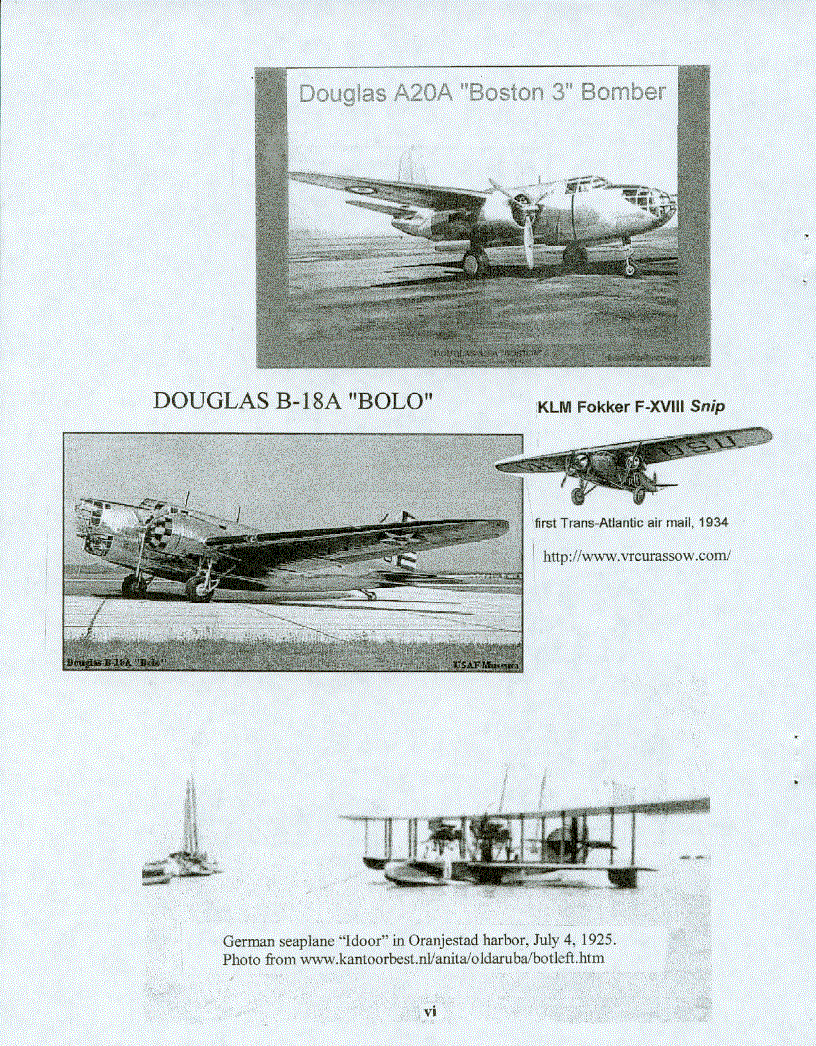

The U.S. Army Air Force, however, provided the first U.S. military presence in the Netherlands Antilles. The 59th Bombardment Squadron’s Flight C, three Douglas A20A twin-engine light bombers, flew from Aguadulce, Puerto Rico to Dakota Field, Aruba, on January 12, 1942. Flight B, three more A20As, flew from Puerto Rico to Hato Field, Curacao the next day. The 2300 foot-long airfields at Aruba and Curacao were dangerously short for A20 operations and had no runway lights.[15]

Forces 1280 and 1291 were initially scheduled to depart from New Orleans on January 10 but were delayed until diplomatic negotiations were fully completed. The Dutch were dissatisfied over command arrangements in the Far East and unwilling to permit Venezuelan participation in the defense of Aruba and Curacao. Colonel Peter C. Bullard, Commander of All Forces Aruba and Curacao, (CAFAC) and his staff arrived in Curacao on January 28 to make final arrangements for the deployment. The task forces finally sailed from New Orleans on February 6[16] bound for coded destinations ALPHA (Aruba) and KAPPA (Curacao).[17]

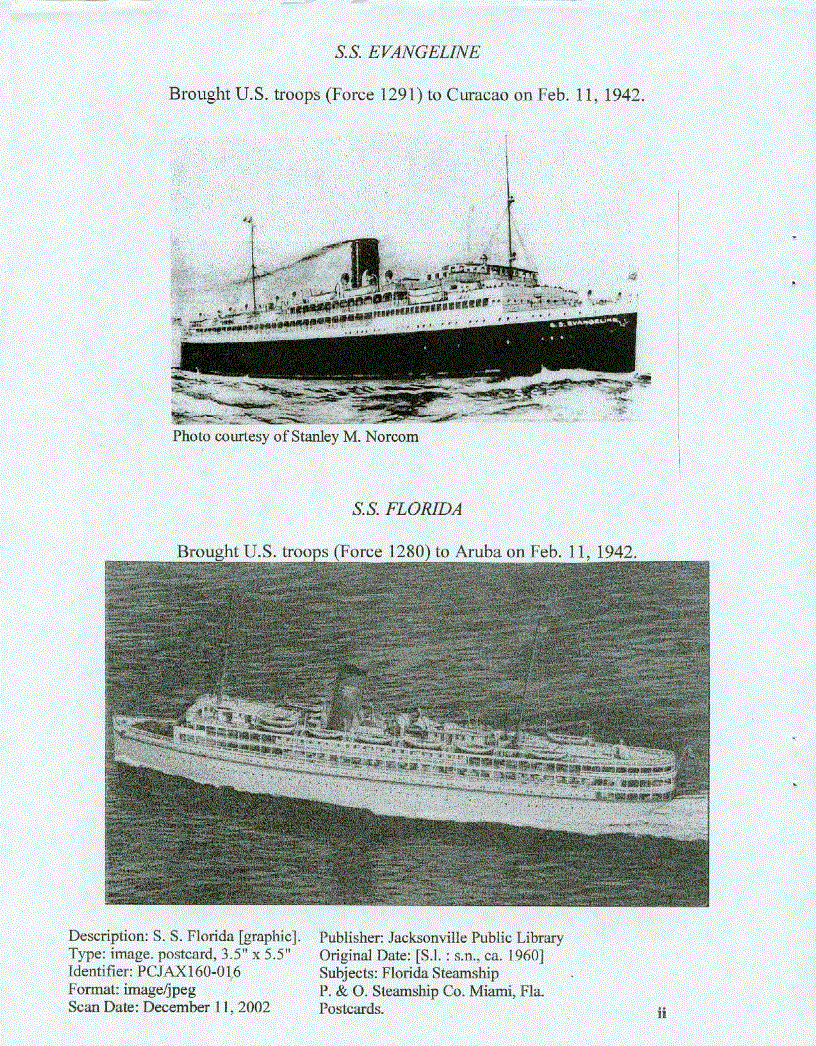

Four ships, Evangeline, S.S. Florida, USS Major General Henry Gibbins, and John R.R. Hannay brought the troops, their weapons and supplies to Aruba and Curacao. The Evangeline arrived with Force 1291 at Curacao on February 11 and the Florida arrived in Aruba the same day with Force 1280. The troop transports had been escorted from New Orleans by the destroyers Blakeley and Barney. The U.S. troops disembarked from the Florida which then took aboard the detachment of Cameron Highlanders. (The Highlanders greatest challenge in Aruba was surviving the farewell parties.) The ship sailed for England on the 13th, stopping in Curacao to take on fresh water. The Gibbins, a munitions and supply ship was about to depart Aruba when the German attack took place. The Hannay brought additional troops to Aruba from Curacao four days after the attack.[18] It is worth noting the history of these ships, given their importance to the story.

The Evangeline was a 5,000-ton passenger ship built in Philadelphia in 1927 for the Eastern Steamship Lines’ intra-coastal service running between New York, Boston and the Canadian Maritimes. She had a crew of 176 and could carry 379 passengers at a speed of 18 knots. She served as a troop transport in WWII, mainly in the Pacific, and was also at times a hospital ship. After the war she was laid up for a while then re-entered passenger service. In 1964 Evangeline was re-named Yarmouth Castle and was on the Miami – Bahamas run.[19]

This ship’s story ended in tragedy on Nov. 13,1965 when she caught fire 60 miles northwest of Nassau. The fire started in a storage room filled with mattresses and paint cans and swept through the ship’s superstructure at great speed. The bridge went up in flames before the alarm could be sounded. By the time the off-duty radio operator tried to return to the radio shack he found it ablaze. Thus there was no S.O.S., the ship’s fire alarms did not sound and the sprinkler system did not activate. The Yarmouth Castle sank with the loss of 87 people, all but two of them passengers.[20]

The S.S. Florida was an ocean liner similar to the Evangeline and was in service from 1931 to 1966. Owned by the Peninsular and Occidental (P&O) Steamship Co., and based in Tampa, FL, it was the first passenger ship to make regular cruises between Miami and Havana beginning in 1931. After the Cuban revolution in 1959, its route was changed to Miami – Nassau. Promotional brochures described the ship as “palatial.”[21]

The John R.R. Hannay was built for the American France Line by the Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co., Kearny, NJ in 1919 and christened the S.S. Waukegan. At some point the 6200 gross ton ship hit the vertical lift bridge of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal and was laid up. It was later sold to the U.S. government and renamed John R.R. Hannay and used as an Auxiliary Cargo Ship (AR32) as well as a troop transport (MSAT). In 1942-43, the last report available said she was supplying bases from Puerto Rico through the Windward Islands to Trinidad.[22]

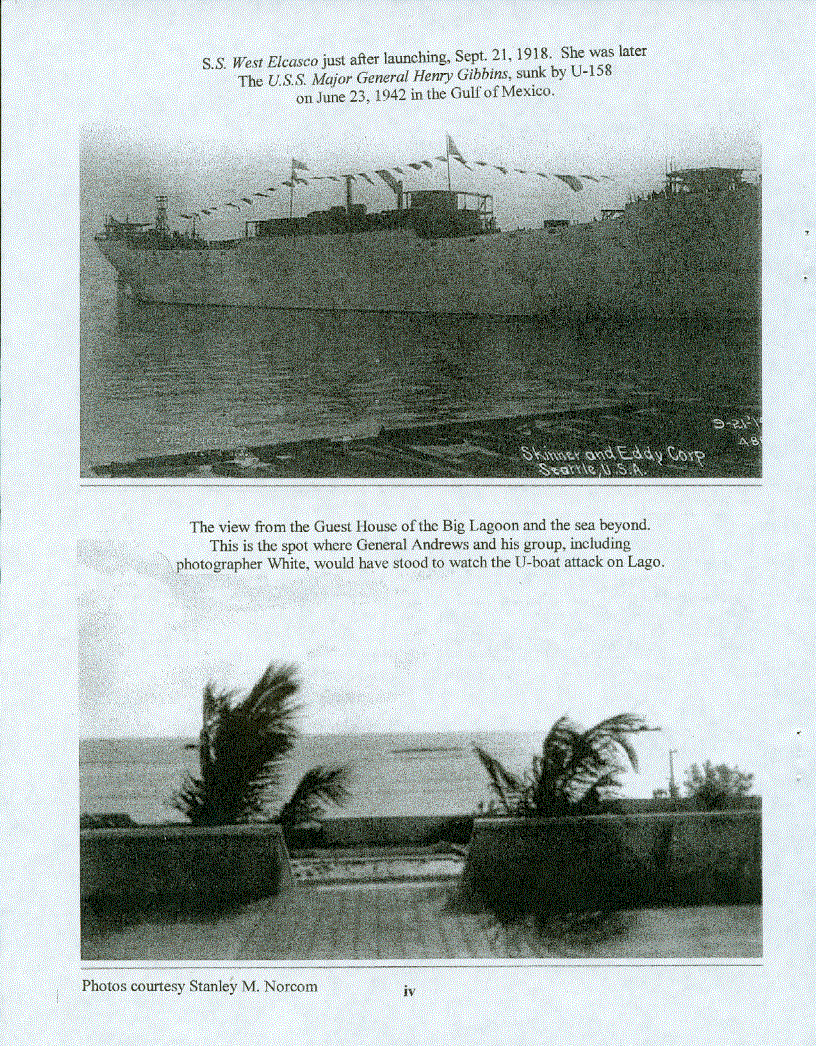

The Major General Henry Gibbins is frequently misspelled Gibbons and can be confused with a second Henry Gibbins troop transport that was launched at Biloxi, MS on Nov. 11, 1942 and had an illustrious career during the war. Both ships were named after Henry Gibbins, U.S.Quartermaster General (1936-1940). Our Gibbins was originally the 6087-ton steam freighter West Elcasco, built in Seattle, WA in 1918, used as a troop transport in WWI and decommissioned in 1919. Its name was changed in about 1941 when it was sold to the U.S. Army which used it as a troop transport and supply ship. It had a short career after the attack on Aruba as it was sunk by U-158 in the Gulf of Mexico about 375 miles west of Key West, FL on June 23, 1942. The freighter was on route from Buenaventura, Colombia to New Orleans with a cargo of coffee when it was torpedoed twice. The ship’s crew of 47 and the 21 U.S. Army guards abandoned ship after the first torpedo hit. All were rescued. U-158, however, soon met a different end. It was bombed and sunk west of Bermuda by a U.S. Navy PBM Mariner one week later. There were no survivors.[23]

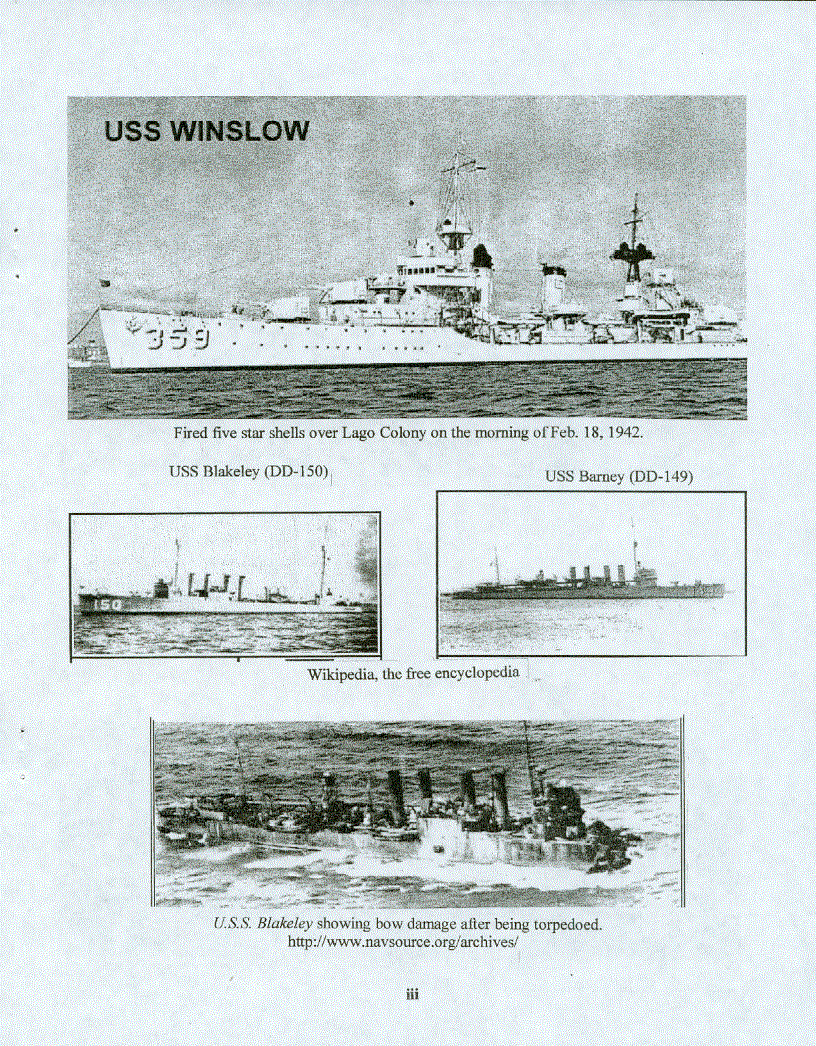

The Blakeley (DD-150) was a four-stack Wickes class destroyer launched in 1918 and named for Captain Johnston Blakeley. The U-156 later encountered it on patrol off Martinique on May 25, 1942 and fired two torpedoes. The second one hit and carried away 60 feet of her bow, killing six of the crew and wounding 21. After emergency repairs at Martinique, St. Lucia and San Juan, Puerto Rico, she steamed to Philadelphia where she was given a new bow and completely overhauled. She was decommissioned in July 1945 and sold for scrap in November.[24]

The Barney (DD-149) was also a Wickes class destroyer launched in 1918 and sponsored by Miss Nannie Dorin Barney, great-granddaughter of Commodore Barney. Between December 1941 and November 1943 she escorted convoys in the Caribbean. It was damaged in a collision with the Greer (DD-145) on September 18, 1942. After repairs, first in Willemstad, Curacao then at the Charleston Navy Yard, the Barney returned to escort duty in the Caribbean and the Atlantic. She was decommissioned in November 1945.[25]

NAZI GERMANY GOES ON THE ATTACK

According to author Michael Gannon, the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor must have stunned Adolph Hitler as much as it did Franklin Delano Roosevelt. A declaration of war would have been expected, but a carrier strike across 3,200 miles of open sea against America’s main battle fleet was a complete surprise. The news also must have shocked Admiral Karl Doenitz, commander in chief of the U-boats, who was in his headquarters, a chateau at Kernevel on the mouth of the inner harbor of the German occupied French port of Lorient. The Admiral went to his maps in his Situation Room and found that it was 3,000 nautical miles from Lorient to the east coast of the U.S. Doenitz calculated that his largest Unterseeboote, types IXB and IXC could make the trip and still have fuel for operations. The IXC, for example could reach the vicinity of New York harbor and still have 110 cubic meters of diesel fuel available for 15 days of maneuvers. He also noted that the IXC class submarine could reach the oil rich depot of Aruba in the Dutch West Indies and have 65 cubic meters of diesel available, enough for almost 9 days.[26]

In late December the German Admiral launched Operation Paukenschlag (“Operation Drumbeat”) with five U-boats, 66, 109, 123, 125 and 130 setting sail for the U.S. East Coast. The first to arrive and sink a ship was U-123 skippered by Kapitanleutnant Reinhard Hardegen. The victim was the Panamanian flag, Norwegian crewed, tanker Norness which was torpedoed 40 miles west of the Nantucket Light Ship on January 14, 1942.

The luck of Lago might have already been in play at this early date. The tanker Esso Aruba, with a full cargo of Lago-processed petroleum, was just on the landward side of the Norness when that ship burst into flames. Later the First Mate of the Esso Aruba said a torpedo had passed just in front of his ship at about the time the Norness was struck. (Hardegen fired five torpedoes at his target and two missed.)[27] This writer, two days shy of age five, was aboard the Esso Aruba with his mother making the trip because he needed the attention of an ophthalmologist and there were none in Aruba. He remembers being awakened, putting on a cork life jacket, looking out of the cabin porthole and seeing the whole skyline ablaze. It was just a matter of timing that had kept the Esso Aruba from being the first ship sunk by a Nazi U-boat in U.S. coastal waters in WWII.

While Operation Drumbeat’s wolf pack was causing havoc on the U.S. East Coast, the German submarine command turned its attention to the southern Caribbean. It was mid- January 1942 and time to implement “Operation Westindien” which would be carried out by the Neuland Group of five IXC long range U-boats. These submarines were over 240 feet long, had a surface speed of over 18 knots and could carry 25 torpedoes. The targets were the refineries on Aruba and Curacao, ships sailing between Lake Maracaibo and the refineries and the shipping lanes around Trinidad. The undersea boats and their skippers were U-67 (Gunter Muller-Stockheim), U-156 (Werner Hartenstein), U-502 (Jurgen von Rosenstiel), U-161 (Albrecht Achilles) and U-129 (Asmus Nicoli Clausen). The first three, which would target Curacao, Aruba and the route from Maracaibo to Aruba, sailed from Lorient on January 19. The 161 left on January 24 and the 129 sailed on January 25, both bound for the Trinidad area.[28]

The Neuland Group had detailed information about their targets. A War Operations Report (BdU) for U-156 dated January 15 reads: “The situation in the Aruba, Curacao and Trinidad areas was discussed by 2 merchant ship captains who have good knowledge (Lt. Cdr. Kregohl of the Supply Group West and Capt. Struewing of KMD in Hamburg.)” Twenty-six days later, on February 10, a BdU on the U-502 noted, “Spanish ship’s officer (Naval Reserve Officer) reported on harbors in Curacao: open, not mined, no black-out, large stores of petroleum on shore. 20-25 tankers, mainly enemy, always there.”[29]

German intelligence reports also came in from other sympathetic sources. One of them was probably Wilhelm Jens Christian Jensen, Chief Engineer of the M.S. Hanseat, operated by Standard Oil Company. Jensen, a Dane, was the subject of several intelligence reports forwarded to the Department of State by the American Consul in Curacao, John Huddleston. He was described as aggressively pro-German and had relatives in Buenos Aires who had been in trouble for Nazi activities. A fellow crew member, British, made two reports on Jensen’s activities to British Consular officials in Bermuda and later on December 15, 1941 in Buenos Aires. In the latter report the informer said Jensen had obtained the tanker’s call letter and might have passed it on to the Nazis.[30]

On the 26th of January the Caribbean Defense Command headquarters at Quarry Heights in the Panama Canal Zone received a naval intelligence report that “a large number of German submarines had entered the Caribbean Sea, destination unknown. The radioed report did warn that ‘attacks on tankers from Venezuela, Curacao and the vicinity [of] Trinidad [are] possible.’”[31] The next two weeks passed without incident in the Aruba-Curacao area and the warning was apparently forgotten.

ARUBA ON THE BRINK

As the U-156’s two diesel engines pushed the German boat past the north coast of Guadaloupe and into the Caribbean on about February 10[32], the atmosphere in Aruba was one of expectation as it seemed everyone on the island already knew that the Yanks were coming. The movement of the U.S. troops from New Orleans to the Netherlands West Indies was no longer a secret by February 7. On that date U.S. Army contract employees Albert M. Mayer and a Mr. McIver arrived at Dakota Field on a KLM flight from Barranquilla, Colombia. Mayer told a number of people at the airport that he was there to supervise the unloading of the freighter and troop transport which would soon be arriving from New Orleans. American Consul Myles Standish took several notarized depositions later which described the situation. The following is part of the statement from Lago refinery official Whitney C. Colby:

“That at about noon, February 7, 1942, I was in the waiting room at the KLM airport, Dakota Field, Aruba, West Indies, when a person later identified to me as Albert W. Mayer, Marine Superintendent, United States Army Transport Service, arrived. I had occasion to be at the KLM airport to meet incoming friends from Venezuela and prior to arrival of the plane, a junior employee of the company, Mr. Val Linam, who was also at the airport to meet other friends, told me that he had just met a man who was to be in charge of unloading operations when the freighter ship and troop ship arrived from New Orleans.

“I immediately told him we should not discuss such a matter further at that time and asked where he got his information. He indicated that it was from a Mr. Mayer who was then at the airport sitting with a group of Air Corps officers, which group included at least one wife of our American colony…

“Mr. Linam asked if I wished to meet Mr. Mayer and I indicated I would because of the disclosures that had already been made. When introduced to Mr. Mayer I identified myself as an official of the company and Mr. Mayer immediately started asking questions and frequently indicated that he was here to supervise the unloading of a freight ship that was soon to arrive, and when he started on this line I immediately held up my hands and suggested that such matters should be discussed under different conditions and not at the airport…

“Upon my return to the colony and contacting the American Consul, I explained to him over the telephone what had transpired at the airport and suggested that he might like to take steps to see that Mr. Mayer was advised on steps on how to handle himself, which the Consul indicated that he had already done, and Mr. Mayer was then in his office.”

Similar statements were taken from Linam, Henry Slaughter and Air Corps Lieutenants Lazenby, Rowley and O’Connor. A contrite Mayer apologized for his actions saying that he did not know it was dangerous to talk in Aruba and that the information he was passing on had been in U.S. newspapers. In a cover letter to Lt. Col. Charles R. Jones, Commanding Officer, Force 1280, Consul Standish described why he acted quickly: “This action was taken because of the rapidity with which news spreads on this small island and because of the possible presence here of enemy agents. It is interesting to note that Mr. Mayer arrived at Aruba on February 7, and the information was public knowledge by February 9. Even small children were heard on the latter date discussing the expected arrival of the United States Army transport on February 10.” Standish attributed Mayer’s loose talk to his “lack of experience in Government employ” and suggested “he is now a more dependable employee…”[33]

Standish was a seasoned diplomat whose fame in diplomatic history comes from his performance as Vice Consul in Marseilles, France in 1940 under Hiram Bingham IV. He was in charge of passports and visas and issued visas to Jewish and other refugees seeking to escape France to Portugal. He was instrumental in rescuing German novelist Lion Feuchtwanger from a French-German internment camp.[34]

On February 11 a wiser Albert Mayer went to work supervising the disembarking of some 850 soldiers and their equipment from the Florida and later the Major General Henry Gibbins. The troops went to the Sabaneta camp vacated by the Cameron Highlanders. Mayer, whose arrival was a perfect illustration of the WWII slogan “Loose Lips Sink Ships”, soon redeemed himself as Standish reported in Secret Telegram #51 on Feb. 13, “The HENRY GIBBINS arrived 11 a.m. yesterday began discharging on 24 hour basis soon after arrival. Inadequate dock facilities, complete absence experienced stevedoring gangs, and nature cargo require continued services of Mayer. With good luck expect GIBBINS to sail February 18th or 19th.”

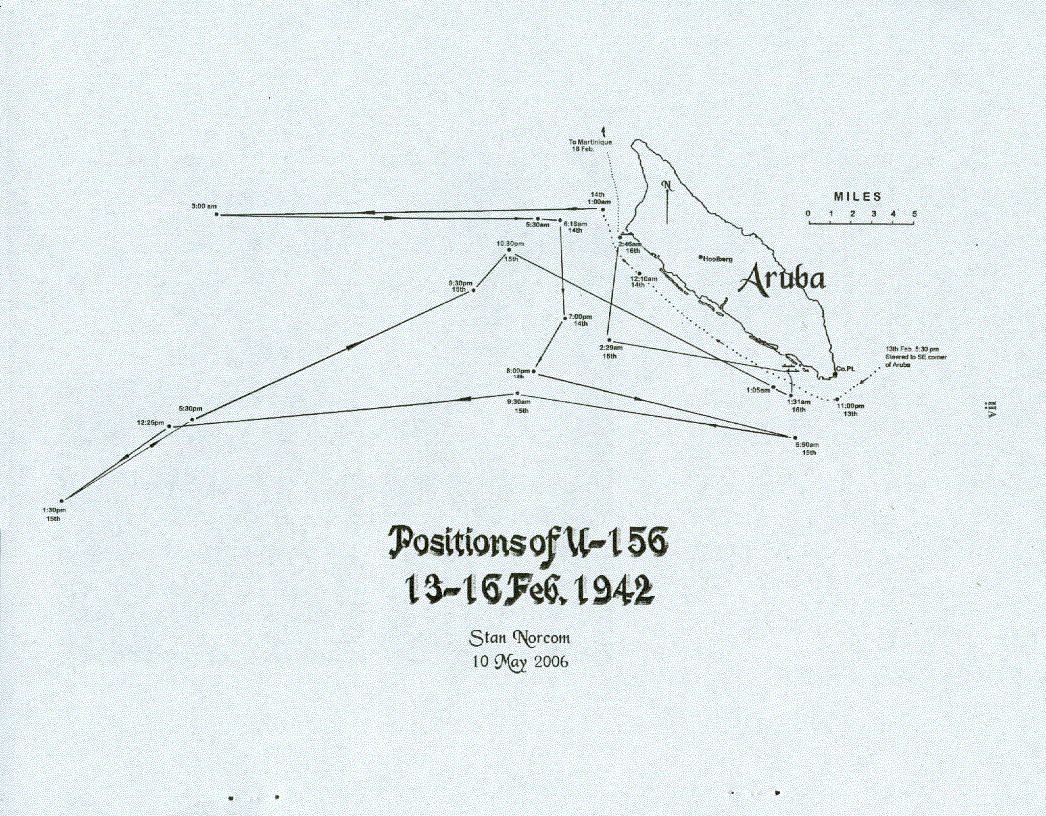

Meanwhile, the German U-boats were drawing closer to their targets. On the evening of February 13, Kapitanleutnant Werner Hartenstein brought U-156 to the surface and steered for Aruba’s Colorado Point light. At 20:30 hours* the submarine moved past Lago refinery. Hartenstein and his officers noted that “The refinery was well lighted, four large tankers were in port and three were at road stead, and traffic also moved at night.” U-156 then moved down the island’s south coast to Oranjestad where Hartenstein dove his boat and went into the mouth of the harbor, but there was little to be seen through the periscope. Leaving Oranjestad, he proceeded to the southwestern tip of the island and noted a lone tanker tied up to the Eagle Refinery’s 777-foot long pier.[35]

(*A U-156 position map based on various reports accompanies this article. Until the vessel’s official log is completely available there will remain discrepancies in time of location.)

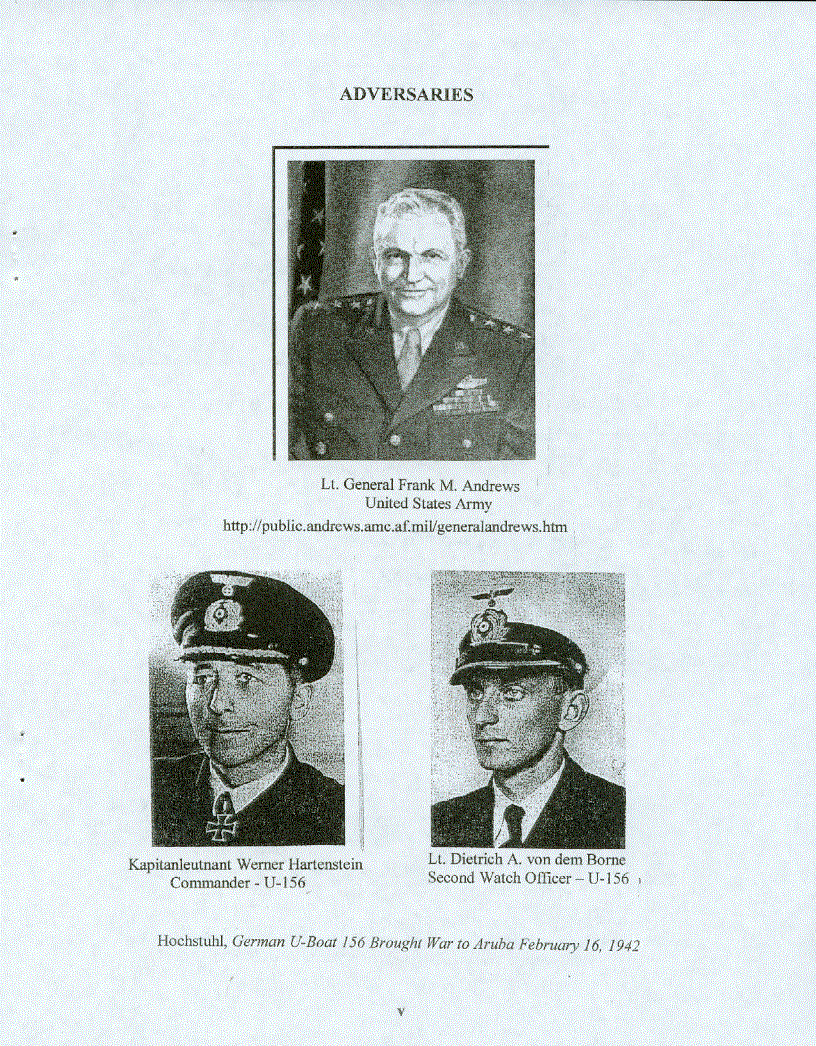

Although historians have not made much of it, Lago was in luck on the 15th with the arrival from Panama of the Commander of the Caribbean Defense Command, Lieutenant. General Frank M. Andrews. General Andrews was on a routine inspection tour and his retinue included media, among them Associated Press photographer Herbert White and Collier’s magazine roving editor, Walter Davenport. Andrews was one of the founding fathers of the U.S. Air Force. The following year he would become the Commander of the U.S. European Theater of Operations before his untimely death in a plane crash along the Icelandic Coast. The name Andrews echoes today whenever the President of the United States leaves Washington by air, but few remember that he was there, in Aruba, and took command when the first shells were fired at a land target in the Western Hemisphere in World War II.[36]

At the time of Andrews’ arrival, there was no unity of command on the American side between the Army and the Navy. Nor had the American forces been placed under the Dutch military commander. Col. Bullard, stationed in Curacao, was to cooperate closely with the Governor and act under his general supervision provided he could do so without jeopardizing the success of his mission. It would not be until March that there would be a unified command of all Dutch and American forces under an American officer (Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf).[37]

The Germans were also having command decision problems in regard to the orders the submarines of Gruppe Neuland 176 would carry out. Originally, as Hartenstein had told his crew as they approached Aruba, the plan was to attack the refineries on Aruba and Curacao and then engage tankers between the Netherlands Antilles and Lake Maracaibo. But then this message was logged in at 06:10am (Aruba time) February 15:

“x. Officer entry: to Neuland boats. 1.) The principal assignment is to attack ship’s targets. 2.) If this attack is successful, then artillery attack against land targets can be made on the morning of Western Hemisphere time should opportunity for this be favorable and 3.) When no ship targets are encountered artillery attacks against land targets may be made toward evening of Western Hemisphere time.”[38]

The Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy, Admiral Raeder had favored shelling the refineries first. The Commander of the U-Boats, Admiral Doenitz, went against his superior and later wrote this explanation in his memoir: “I had decided against issuing an order to commence submarine operations by shelling the tank installations, as there was a danger that such shelling, which might or might not be successful, would do away with the element of surprise and spoil the chances of sinkings.”

LAGO UNDER ATTACK

As night fell on the 15th Lago residents felt comfortable. The troops had arrived and their large and small guns, field telephone wires, searchlights and large stockpiles of shells were starting to appear in various places. Among the armaments were four 155mm howitzers which would provide a formidable defense once they had been installed on Colorado Point. In San Nicolaas harbor the Major General Henry Gibbins had finished unloading the weapons, supplies and munitions allocated for Aruba and was preparing to depart for Curacao. Among the ships docked at refinery piers was U.S. Navy tanker Chenango (AO-31), formerly the Esso New Orleans.[39]

General Andrews and his entourage settled down at the Guest House, a well-appointed Lago Colony bungalow next door to the home assigned to the refinery’s deputy manager and known later as the Mingus house. The front patio overlooked Rodgers Beach and the group could see the Big Lagoon in front of them and the reef in the background and beyond it the anchored lake tankers Pedernales and Oranjestad.[40]

While the Colony residents were going to bed, some of them having attended a reception/dance at the Officers’ Club in Sabaneta for the newly arrived troops, Kapitanleutnant Hartenstein was steering the U-156 (on the surface) on an easterly course toward Oranjestad. At 11:30 p.m. he passed Eagle pier where he noted “an illuminated tanker loading.” (Arkansas). He then proceeded to “Nicolas Harbor.”[41]

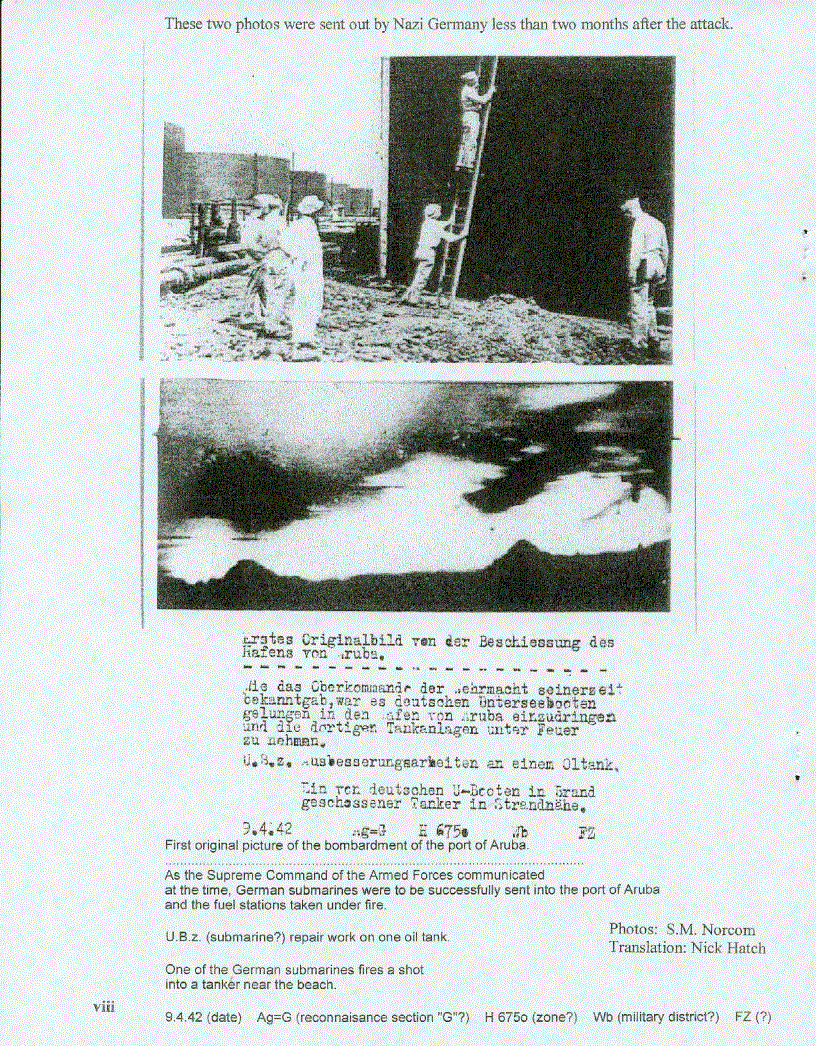

It was 01:31 on February 16 when the U-156, now on the surface, fired its first torpedo which hit the side of the Pedernales and turned it into an inferno. Two minutes later a second torpedo sank the Oranjestad. The submarine’s deck gun crew then prepared to fire their 10.5 cm cannon at the well-lit refinery. That was when their luck ran out and Lago’s began. The first round exploded in the barrel, putting the gun out of commission, fatally wounding seaman Heinrich Businger and wounding the gun’s crew chief, Oberleutnant Dietrich von dem Borne. The round exploded because the tampion which plugged the muzzle of the gun, protecting it when the sub was submerged, had not been removed. The other gun crew, manning the smaller, 37mm gun, managed to fire 16 rounds, some of them tracers, in the direction of the tank farm before Hartenstein ordered a cease fire and turned the U-156 on a westerly course toward Oranjestad. In his log entry, Hartenstein deplored the fact that the 37mm had not been equipped with "“illuminated night sight-lights.” One shell hit an oil tank (#112), denting its steel plating, a second was reported to have hit a house north of the lower tank farm.

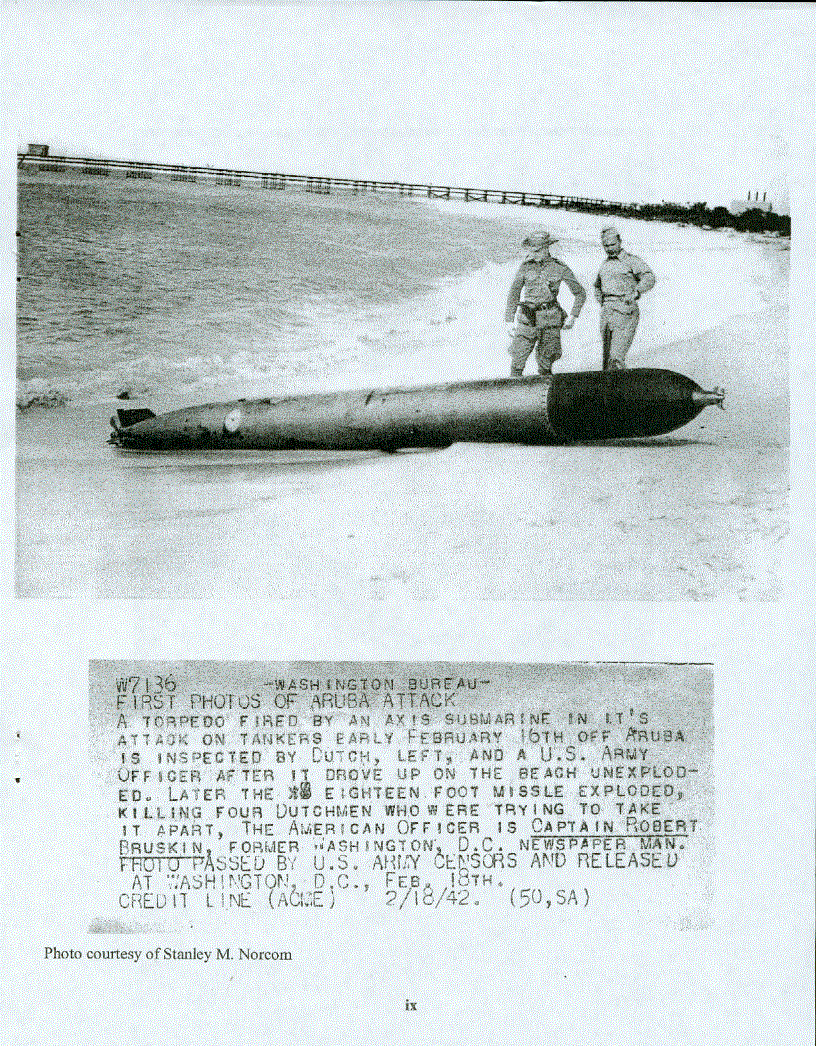

Off Eagle pier he fired three torpedoes at the Arkansas. One hit the empty Texaco tanker; the other two went astray, one coming up on the beach where it would later explode killing four members of a Dutch Marine demolition team.[42]

Meanwhile, the other two U-Boats in the area were also busy on February 16. Von Rosenstiel’s U-502, in the shipping lane between Maracaibo and Aruba, sank the lake tankers San Nicolas and Tia Juana as well as the Panamanian flag tanker Monagas. One mile off Curacao, the U-67 damaged the Shell Oil tanker Rafaela,.[43]

Time Magazine’s February 23 issue reported on the shelling of Lago and carried this eyewitness account from Associated Press Photographer Herbert White: “A mile offshore a submarine lay on the surface, pouring shells at the island. Already two tankers in the harbor were on fire, flaming oil spread over the water. Said Photographer White, ‘The harbor scene was like a raging forest fire right in your own front yard… The blaze was shooting up high over the waterfront. I could see the decks of [one] ship as a mass of flames.’” (This monumental error of placing the tankers within the narrow confines of the harbor instead of anchored in the roadstead would be a “fact” repeated by several historians in the years to come.)

THE AMERICAN RESPONSE

Lago and its defenders were caught completely off guard. Although the 37 mm anti-aircraft automatic weapons of Battery G, 213th Coastal Artillery, had been set up on a Lago pier and at nearby Camp Sabaneta, they were unable to open fire because of the thick smoke from the burning tankers. The 155mm howitzers were still sitting on the docks where they had been unloaded.[44]

The American forces had only one card to play – three Douglas A20A light bombers stationed at Dakota Field and three more at Hato Field, Curacao. Although these planes were not designed or equipped for anti-submarine warfare (no radar, no depth charges), they were a deterrent that would keep a U-boat under water and on the defensive.

Even though the fields on both islands were being lengthened, they were still graveled with no runway lights and were unsafe for night landings. Nevertheless, the first A-20 was sent off about an hour after the attack, the second about 30 minutes later and the third about an hour later. The SCR-268 radar ashore picked up targets at sea some 35 miles offshore and one of the A-20s went to the area and dropped a flare. Because the bombers had a flying range of slightly less than two hours, the first A20 was forced to land at Maracaibo. That caused a problem with the Venezuelans because their country was still neutral and U.S. military aircraft required at least 24 hours prior approval before landing there.[45]

The Curacao A20s took off at daybreak preceded by the only Dutch bomber, a converted Fokker tri-motor airliner known as the “Snip.” At Hato Field the alert had come several hours after the attack because the telegraph station was closed at night. At about 9:00 am three twin-engine B-18 bombers arrived in Aruba from Trinidad and four other B-18s from the 40th Bomber Group at Borinquen Field, Puerto Rico landed in Curacao. General Andrews would later write to General Marshall saying, “It was fortunate we had airplanes there, otherwise the oil plants would have been in for a good shelling.”[46]

Another fortunate event was the fact that much of the Henry Gibbins’ cargo of munitions had been unloaded ahead of schedule and that its time of departure for Curacao was delayed because the crew apparently demanded a coffee break before leaving. Historians have made much of the “fact” that the Gibbins was a munitions ship said to be carrying 3,000 tons of TNT. That is a gross exaggeration, but nevertheless had the attack occurred earlier, and had the Gibbins been hit by gunfire and exploded, the damage would have been catastrophic.[47]

Consul Standish summarized the situation on February 16 in this Confidential Telegram #54 sent at 5 pm:

“Inform Quartermaster General, transport GIBBINS finished loading 1 a.m. today was on point sailing for Curacao when enemy action began. Vessel remaining Aruba until proper escort can be provided. Naval force expected tomorrow from Puerto Rico. General Andrews, who arrived yesterday afternoon on inspection visit, remained Aruba until this afternoon, having established temporary command post here and directed action American armed forces. Six heavy bombers from Trinidad and light ones from Curacao arrived. Air force believes it sank enemy submarine early this afternoon off Venezuelan coast by light bomber stationed Aruba but no official confirmation. Apparently submarines attacked these waters in force as sinkings reported off Colombian coast as well. All shipping Aruba ordered remain in port.

“Please telegraph digest my telegram today to Ambassador Caracas who requests report on attack Aruba. Urgent matters prevent my complying. STANDISH”

THE AFTERMATH

The 17th was a much easier day even though the torpedo on Eagle Beach exploded. On the U-156, where seaman Businger had died the day before and was buried at sea, Hartenstein received a message from headquarters giving permission to put Von dem Borne ashore in Martinique and headed his craft in that direction. The gunner had lost a foot and needed proper medical attention.[48] In Aruba the casualty total stood at 51 dead (47 sailors from the lake tankers plus four members of the Dutch demolition team).

It was quiet enough that Consul Standish found time to get a message (#55) off to the State Department asking for more staff help and made this observation to support his request: “When submarine attack these waters has been liquidated expect Lago will request this office transmit all shipping messages as ship losses and actual attack refinery have effected apparent reversal company’s attitude toward government assistance.”

The U-502 was still in the area and its report to headquarters for the 17th noted “Observation on Nicolaashaven: blacked out, no traffic, air patrol, three patrol boats, impossible to use ship’s guns.”[49] The attempt by U-502 to take further action against Lago refinery was recorded in its report and noted later by Admiral Doenitz, who wrote in his autobiographic memoirs, “The second boat which tried to bombard the oil tanks at Aruba was forced to retire and break off the operation when patrol vessels appeared.” A local paper reported the next day, “For a second night Aruba was blacked out and it was by no means an exercise, but a bitter necessity… We are glad to say that the people are behaving splendidly… The management of the Lago announced that at least 7 tankers have been torpedoed with a possible loss of about 59 persons.”[50]

February 18 would prove to be a more dramatic day because just after mid-day a U-Boat surfaced in the still waters just off Oranjestad harbor. Clyde Harms, then a 10-year old schoolboy, witnessed it and later wrote, “There was a great commotion in Oranjestad along the shore where are now located the Seaport Market place and the Wilhelmina Park. A German submarine had emerged right in the middle of the bay as hundreds of us school children were returning to Juliana School after our lunch break… It is an experience that I shall never forget…”[51]

Another witness was Lt. Ira Matthews, co-pilot on one of the twin-engine B-18s of the 40th Bomb Group that had been called in by General Andrews. Matthews and two other crew members were “wolfing down a cold meal of canned rations in a windowless shack at the upwind end of the gravel surfaced Aruba airport” while the plane was being refueled. (They had just completed a six-hour sortie escorting four lake tankers from Las Piedras, Venezuela to Aruba.) Suddenly the submarine was spotted and the crew made haste to take off, almost leaving the pilot, Col. Palmer behind. By the time they got to the submarine’s last position, the U-boat had submerged and moved away. The aviators dropped four depth charges, but did not record a hit.[52]

In spite of these eyewitness accounts, whether the submarine was actually in Oranjestad Harbor has been a subject for recent debate. If the U-502 log were available for that date it might put an end to the discussion. There is also conjecture in regard to which submarine it was. U-502 and U-67 were the only boats in the area with the latter focusing on Curacao. Admiral Doenitz’ BdU for Feb. 17 mentions both U-boats and says “U-502 was sent to Aruba as U-156 had a breakdown.” Thus in all probability it was U-502, the same sub that had been observing San Nicolaas harbor the night before.

The commotion the submarine caused was minor in comparison to the action taken by the U.S. Navy destroyer Winslow at 5:30 a.m. on the morning of the nineteenth. The Porter class destroyer, called in from Puerto Rico, was a relatively new ship (commissioned 1937), heavily armed and able to cruise at 35 knots.[53] The Winslow fired five star shells to illuminate a possible submarine off Lago Colony. The empty shells fell in the colony causing slight material damage but considerable hysteria among the residents. One shell casing passed through the Esso Club library and littered half the club with splintered wood. A second one went through Ted Schelforst’s room in Bachelor Quarters #6, passing within inches of his feet as he lay asleep. No submarine was sighted. (Some accounts mix this event with the attack on the 16th and it has also been characterized as a second U-boat attack.)

Later in the morning the Winslow dropped depth charges to clear the approaches to San Nicolaas harbor as the first convoy of three tankers was standing out to sea. One ship, the Panamanian flag tanker Typhoon had just passed through the opening in the reef when two heavy explosions shook the area. The ship had been in the harbor since before the U-boat attack and the crew attributed the explosions to enemy action. They immediately lowered the lifeboats and rowed back into the harbor![54]

The destroyer then proceeded to deal with another problem. The Spanish flag tanker Zorroza was anchored about eight miles from the Paraguana Peninsula, or about 20 miles SSW of Aruba. A party from the Winslow boarded the vessel but found nothing out of order. Three days later, Consul Standish would report, “Spanish tanker ZORROZA still off Cape Romana. Local navy units feel she may be assisting enemy and wish remove her from present anchorage. Suggest commander naval forces here be instructed invite vessel proceed under escort Stannas Bay Curacao to provide safe anchorage in these submarine infested waters.”[55]

By the next day, Consul Standish was able to report that “the enemy has been relatively inactive past three days view intensive allied air and naval operations these waters. Admiral Hoover was here yesterday afternoon stated no increased defense forces can be expected.

“Evacuating at Lago expense those American women and children who wish return United States. Travel by air via Maracaibo and Barranquilla to Miami will begin this afternoon or tomorrow a.m…. Expect evacuate about 150 persons next three days. Lago handling details. Inform Quartermaster General U.S.A.T. HANNAY arrived 2 p.m. from Curacao with additional troops for here.”[56]

The Consul was also able to report that the Eagle pier would be closed for about three weeks and that the tanker Arkansas was now in San Nicolaas harbor undergoing minor repairs and could make an American port for major repairs on its own steam if a salvage tug and naval escort were provided. This information was passed on to Texaco’s New York office by Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles. Texaco responded by thanking Welles for “transmitting to us certain data with respect to our tanker “ARKANSAS”, which unfortunately met with an accident early the morning of February 16th.”[57]

The threat to the Lago refinery was now over, but the high seas continued to be dangerous. Standish cabled Washington on Feb. 22 to report that there were still five submarines believed to be in the area and that the Norwegian tanker Konesgaard had been torpedoed the day before off Curacao and that today “Dutch coast patrol vessel fired unsuccessfully on submarine which had surfaced just off entrance San Nicolaas harbor.” In messages sent on the 24th Standish reported that the American motor tanker Sun had been torpedoed fifty miles northwest of Aruba at 10:00 am on the 23rd and that the Panamanian tanker Eulalia (Thalia?) had been sunk in the same area. Although badly holed amidships, the Sun was able to make it to San Nicolaas harbor. U-67 was given credit for the Norwegian ship while U-502 claimed the Sun and Thalia.[58] In April there was an attempt to shell the Curacao refinery and submarine activity continued in the Caribbean until 1945.

WHY LAGO WAS LUCKY

Most accounts attribute the Lago refinery’s good fortune in surviving the surprise attack on the night of February 16, 1942 to two facts: The 105 mm. deck gun on the U-156 blew up with the first shot, and the munitions ship Gibbins delayed its sailing. But that is only part of the story. If Admiral Doenitz had sent all five of the Neuland boats to the Aruba – Curacao – Maracaibo area they would have taken a much higher toll. The same would have happened if he had concentrated the three U-boats in the area on Lago refinery and the Aruba-Maracaibo lake tanker route.

The matter of timing was also all-important. If the wolf pack had arrived a couple of days earlier, they could have caught the American troops disembarking and the Gibbins unloading its deadly cargo. General Andrews wouldn’t have been there to direct the defense force and call in more aircraft. The Nazis might have been able to torpedo the Florida and send the Highlanders to a watery grave. There seems to have been an intelligence failure on the German side. The arrival time of the U.S. forces had been leaked in advance and there were spies in the area, probably including some of the crew of the Spanish tanker Zorroza which lingered in the war zone. So, one might have expected the German side to have that knowledge and thus direct a greater effort to attacking the well-lit refinery.

Shelling the refinery after sinking the tankers was theoretically the right decision. Submarines are not artillery platforms, especially at night when a deck gun’s muzzle flash can expose the ship. And as one old submariner once told this author, “for us there are two kinds of ships, submarines and targets.” Doenitz correctly realized that the lake tanker pipeline was the weak link in the Lago operation. By taking out just four of those shallow draft ships, referred to as the Mosquito Fleet, Lago’s production was reduced from 228,000 barrels per day of processed crude oil down to 147,100. It would be July 1943 before the first replacement tanker would arrive at San Nicolaas harbor and production would go back up almost to the pre-war level.[59]

EPILOGUE

The lake tanker Pedernales, the first ship hit in the attack, was never sunk. It was found adrift and abandoned and a tug towed it back to Aruba where the damaged center section was removed and the bow and stern welded together. Shorter by 124 feet, the Pedernales sailed back to the U.S. where she was rebuilt. In October 1942 as the British stopped Gen. Rommel’s Afrika Corps at El Alamein, Lago gasoline was there. A week later when American and British troops landed in Western Africa in Operation Torch, the Pedernales was in one of the convoys of support vessels.[60]

As for the U-boats, all were sunk except for the U-129 which was taken out of service on July 4, 1944. U-67 was sunk on July 16, 1943 in the Sargasso Sea at 30.05N, 44.17W by depth charges dropped from an Avenger aircraft from the escort carrier USS Core (ACV-13). There were 47 dead and three survivors. U-161 went down on Sept. 20, 1943 in the South Atlantic near Bahia, Brazil and all hands were lost. U-502 was sunk in the Bay of Biscay on July 5, 1942 by a British Wellington aircraft. All hands were lost.[61]

U-156’s first combat adventure had been quite a debacle. Three ships, all stationary targets had been torpedoed, but only one was sunk. The deck gun then blew up and the Aruba portion of the mission soon had to be aborted. Nevertheless, after leaving Martinique, commander Werner Hartenstein managed to repair the deck gun by having the end of the barrel sawed off. The downsized gun was then used to sink the freighter McGregor on February 27th and the tanker Oregon the next day. U-156 completed three patrols in 1942, sinking over 100,000 gross tons of shipping which earned Hartenstein the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross and placed him among the top 35 U-boat commanders.[62]

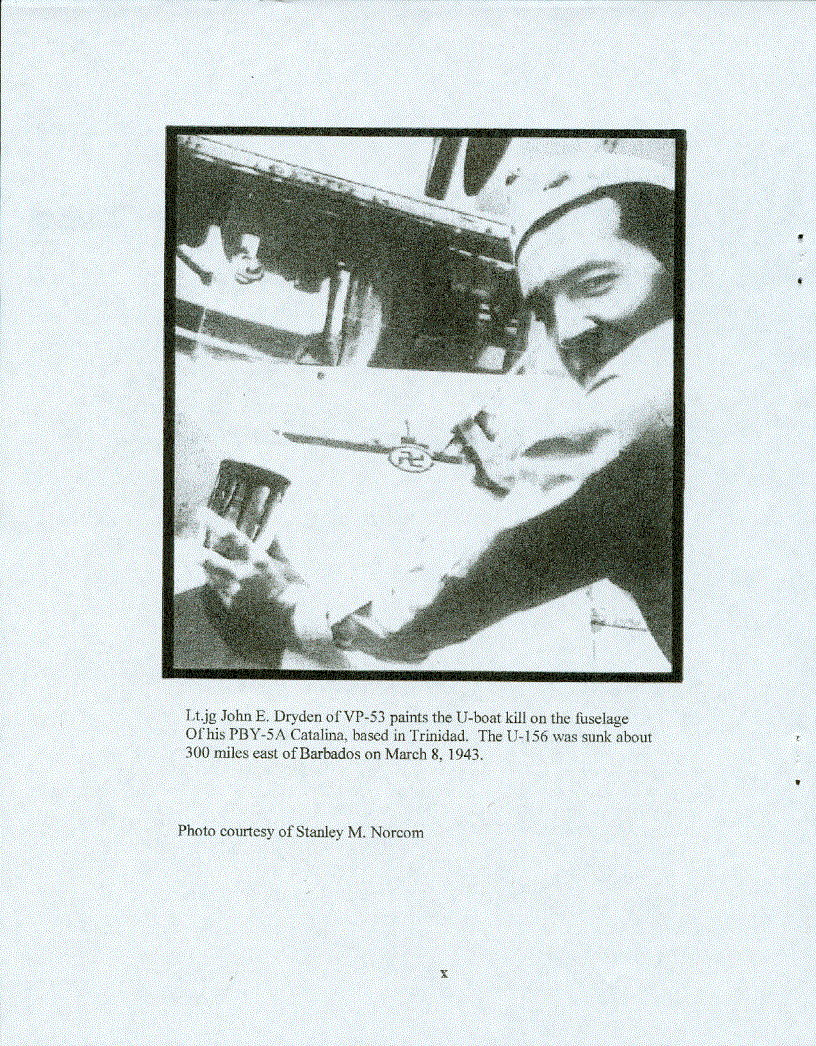

The end of the U-boat and its 33 year-old commander came on March 8, 1943 about 300 miles east of Barbados when it was spotted by a PBY-5A Catalina from Squadron VP-53 based in Trinidad. The white painted flying boat caught the sub by surprise, emerging from the clouds at 1200 feet and a half-mile from the target. The pilot, U.S. Army Air Force Lt. Jg. John E. Dryden, dropped four 350-lb Mark 44 Torpex-filled depth charges that straddled the conning tower and broke the sub apart. The patrol plane sighted survivors, dropped two rafts and an emergency rations kit attached to two Mae West life jackets. Only the smaller, two man raft inflated and five men were photographed in it, but they were never known to be found by surface craft.[63]

Kapitanleutnant Dietrich A. von dem Borne, the only German known to have provided a detailed eyewitness comment on the Aruba attack, became a prisoner of war when he was taken out of Martinique in 1944 and flown to the U.S. where he boarded the S.S. Gripsholm with other Germans involved in a prisoner-of-war exchange. The exchange took place in Barcelona, Spain on May 19, 1944. Von dem Borne later tried to rid himself of the blame for the U-156 deck gun mishap and be awarded the Verwundetenabzeichens (the German equivalent of the Purple Heart.) On January 23, 1945, he filed a compelling appeal explaining how the accident could only be due to a faulty round. The Kriegsmarine turned a deaf ear and he lived the rest of his life with his burden and died in 2005[64].

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author greatly appreciates the valuable information provided by researchers Stanley M. Norcom and Gerard Casius, U-156/502 Roundtable organizer Donald Gray and Sally Kuisel of the U.S. National Archives. Without their help, this report would still be a work in progress.

Ray Burson

Doniphan, MO

June 2006

(Second Edition, April 2008)

FOOTNOTES

[1] Johan Hartog, Aruba Past and Present, (Oranjestad, Aruba, Netherlands Antilles, D.J. De Wit, 1961), p.359, www.netherlandsnavy.nl/Vankin_his.htm

[2] Dan Jensen, “A Short History of Lago Oil & Transport Company, LTD, Aruba, N.W.I.”, Monograph 2003, p.13 and Table 1.

[3] Hartog, p. 360.

[4] U.S. Dept. of State, Publication 1983, “Peace and War; United States Foreign Policy, 1931-1941” (Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office), pp. 531-535.

[5] Hartog, pp. 359-60.

[6] “The War Years at Lago, 1939 – A Summing Up – 1945”, Aruba Esso News, publication of Lago Oil & Transport Co., Oct. 18, 1946.

[7] Hartog, p. 340, www.museumaruba.org

[8] German Foreign Office Memorandum, Oct. 31, 1940, www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/wwii/spain/sp10.htm

[10] William C. Gaines, “The United States Coast Artillery Command on Aruba and Curacao in World War II”, The Coast Defense Study Group Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 2, May 1997, p. 21. (pages are estimates as article was taken from Internet posting.)

[11] Aruba Esso News, October 18, 1946.

[12] Conn, Engleman and Fairchild, The U.S. Army in World War II, Guarding the United States and its Outposts, The Western Hemisphere, Chapter XVI, “The Caribbean in Wartime,” pp. 409-414.

[13] Joint Planning Committee Report, Jan. 13, 1942.

[14] Gaines, pp. 21-22.

[15] Unit Histories, 25th Bombardment Group, 59th Bombardment Squadron, home.satx.rr.com/bombardment/htmdocs/59thbshistorytem.htm E-mail Gerard Cassius to Ray Burson , Feb. 1, 2006.

[16] Gaines, p.22, Conn, Engleman, Fairchild, p.415

[17] Navy Historical Center, www.history.navy.mil/index.html

[18] e-mails, Gerard Casius to Ray Burson, April 7,8, 2006. Telegram #52 (SECRET), Feb. 13, 1942, #59 (SECRET), Feb. 20, 1942, from Consul Standish, Aruba to Sec. State, Washington

[19] “Ships of the World: An Historical Encyclopedia”, Houghton Mifflin, Online Study Center, http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/ships/html

[21] Historical Museum of South Florida.

[23] e-mail Joe MacDougald to Stanley Norcom, Jan. 15, 2006, www.uboat.net

[26] Michael Gannon, Operation Drumbeat, New York: Harper & Row, 1990, pp. xv, xvi.

[27] Ibid., pp. 216-17.

[28] William C. Hochstuhl, German U-Boat 156 Brought War to Aruba February 16, 1942, 60th Anniversary Edition, Oranjestad: Aruba Scholarship Foundation, 2001, www.ubootwaffe.net, e-mail Stanley Norcom to Ray Burson, Jan. 14, 2006.

[29] Stanley Norcom from www.uboatarchive.net www.uboatwaffe.net/sources

[30] Letter from J.F. Huddleston, American Consul, Curacao, to Secretary of State, Feb. 17, 1942.

[31] Gaines, p.23.

[32] Hochstuhl, p.10

[33] Memorandum to the Secretary of State from Vice Consul Myles Standish, Aruba, Feb. 23, 1942.

[34] The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation.

[35] Hochstuhl, p. 11, Gaines, p. 23.

[36] Time Magazine, Feb. 23, 1942, http://public.andrews.amc.af.mil/generalandrews.htm

[37] Conn, Engleman and Fairchild, The Caribbean in Wartime, p. 421.

[38] Hochstuhl, actual U-156 log page inserted after p. 20.

[40] Aruba Esso News, Nov. 8, 1946, p.4.

[41] Hochstuhl, photocopy of U-156 log inserted after p.20, U-156/U-502 Roundtable Newsletter #7, Jan. 29, 2006.

[42] Ibid., pp. 13-14.

[44] Gaines, p. 24.

[45] E-mail Gerard Casius to Ray Burson, 2/1/06, E-mail Norcom to Burson, 5/3/06.

[46] Ibid., also Conn, Engleman and Fairchild, The Caribbean in Wartime, p.423, Ira Matthews, “The Hundred Mile Limit,” www.40thbombgroup.org/matthews

[47] Aruba Esso News, Nov. 8, 1946, Hartog, p.362.

[48] Hochstuhl, p.36.

[49] e-mail, Norcom to Burson 3/21/06.

[50] Aruba Post, Oranjestad, Feb. 18, 1942.

[51] Hochstuhl, p.vi.

[52] Ira V. Matthews, “Submarine in the Harbor”, 40th Bomb Group Association Memories, May 31, 1985.

[54] Telegram #60 from Consul Standish to Secretary of State, Feb. 20, 1942. Aruba Esso News, Nov. 8, 1946, p.8, and Nov. 29, 1946, p.4.

[55] Telegram #62 (Confidential) from Consul Standish to Secretary of State, Feb. 22, 1942, e-mail, Gerard Casius to Ray Burson, Feb. 1, 2006.

[56] Telegram #60 (Confidential) from Standish to Secretary of State, Feb. 20, 1942.

[57] Telegram #57 from Standish to Sec. State, Feb. 20, 1942.

[59] Jensen, “A Short History of Lago Oil & Transport Company,” p.19 and Table 1.

[60] Lee A. Dew, “The Day Hitler Lost the War”, American Legion Magazine, February 1978.

[62] Hochstuhl, p.36, www.ubootwaffe.net

[63] “Analysis of Anti-Submarine Action by Aircraft,” Unit VP-53, Unit Report 7, March 8, 1943 (NARA).

[64] Dew, “The Day Hitler Lost the War.” U-156/U-502 Roundtable Newsletter #7, Jan. 28, 2006.

PHOTOS